Mississippi’s statistics on opioid use resulting in addiction and deaths are bad, but the failure of data to deter abuse is also troubling.

A team of University of Mississippi Medical Center physicians and caregivers is changing the way they offer patients pain relief at a time when an average half million opioid pills are dispensed daily by doctors statewide. The Medical Center’s pain management physicians are partnering with the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior to develop a first-time clinical treatment model around the issue of opioid abuse.

“The goal is not to just rely on one medication, but use a multitude of medications and in doing such, you are able to keep the doses lower of each of the medications and therefore may be able to avoid some of the side effects and complications,” said Dr. William Gusa, assistant professor of anesthesiology and the department’s vice chair for pain services.

Gusa said that their goal is to effectively manage and minimize patients’ pain to give them quality of life and improved function, starting not with opioids, but with other medications or non-medicinal remedies that can protect a patient from addiction. That’s an ambitious program, affecting not just people at home with chronic conditions, but hospitalized patients who may have just been wheeled from the operating room.

“The mindset change of using opioids only as a rescue drug is already in place,” said Dr. Ken Oswalt, assistant professor of anesthesiology and leader of the Medical Center’s acute pain service. “We are limiting the use of opioids in the hospital now.”

The staff of Dr. Douglas Bacon, professor and chair of the Department of Anesthesiology, is spearheading the effort to build and implement the treatment model with assistance from the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, led by professor and chair Dr. Scott Rodgers. Development of the model has the backing of UMMC’s top leadership.

Gusa said that they are looking at acupuncture and other non-medicines, such as physical therapy and occupational therapy, however, he said there’s not a structure right now to incorporate those.

“The problem with a lot of these therapies is that insurance companies have decided not to cover them,” Gusa said. “So, although we have effective tools, it’s hard to get patients to buy in if they don’t have the resources to spend that money on their own.”

Plain and simple, Bacon says, doctors as a community “prescribe way too much opioids.”

Their work comes as the state Board of Medical Licensure is proposing an overhaul of regulations to the prescribing of opioid drugs, a policy shift that has attracted both criticism and praise. Twenty-four states have passed laws limiting opioid prescriptions, but Mississippi isn’t one of them.

On Feb. 1, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services proposed a far-reaching change that would put new limits on pharmacies filling opioid prescriptions for Medicare beneficiaries. It calls for pharmacies to restrict how much opioids Part D Medicare plan participants can receive, and would limit the number of pills in an initial prescription for acute pain.

The state Board of Medical Licensure’s proposed changes would mandate that physicians prescribe the lowest effective dose of opioids for acute pain and not more than a 10-day supply. The policy also would discourage physicians from prescribing more than a three-day supply, and would allow an additional 10 days if clinically necessary, but with a new prescription and documentation of why it’s necessary.

The proposed changes also would include a requirement that providers run the name of each patient receiving an opioid prescription through the state’s online prescription monitoring program to check whether the patient has already received prescriptions from other providers. That regulation would apply to patients coping with acute or chronic non-cancerous and non-terminal pain.

“It’s problematic because as we can all agree you don’t want a primary care physician doing an open heart surgery,” Gusa said. “Obviously a cardiothoracic surgeon should be free to do those types of things, there shouldn’t be restrictions on that.”

The proposals include a requirement that patients be drug-tested each time they receive a Schedule II narcotic for chronic non-cancer, non-terminal pain. At a minimum, opioids, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis would be tested.

“That’s a big change,” Oswalt said. “The current thinking is to decrease the adverse effects of opiates. How do we do that and provide good pain relief?”

Physicians also have a responsibility to treat those who are addicted, Rodgers said.

“We’re talking about pain management and addiction, but there hasn’t been a formalized program to manage addiction at UMMC,” Rodgers said.

Under development is a 40-hour-a-week outpatient clinic for treatment of substance abuse, plus designating some Medical Center inpatient psychiatry beds to those sick enough to warrant hospitalization.

“You need counselors, social workers, and psychologists on the health-care team,” Rodgers said. “The notion of 90-day rehabilitation care is just not true. There’s a very high relapse rate. What works is outpatient services, and it has a much lower relapse rate.”

The goal is to prescribe opiates as a last resort when other remedies don’t work. Cancer patients, however, are not part of that discussion. “Cancer legitimizes the pain issue. Non-cancer pain does not,” Oswalt said.

Here’s what UMMC pain management providers are doing as they fine-tune a new treatment model and change the Medical Center’s culture of pain management:

- They’re treating pain with non-pharmaceuticals. Examples are acupuncture, behavioral therapy and counseling, physical therapy and occupational therapy, plus patient education.

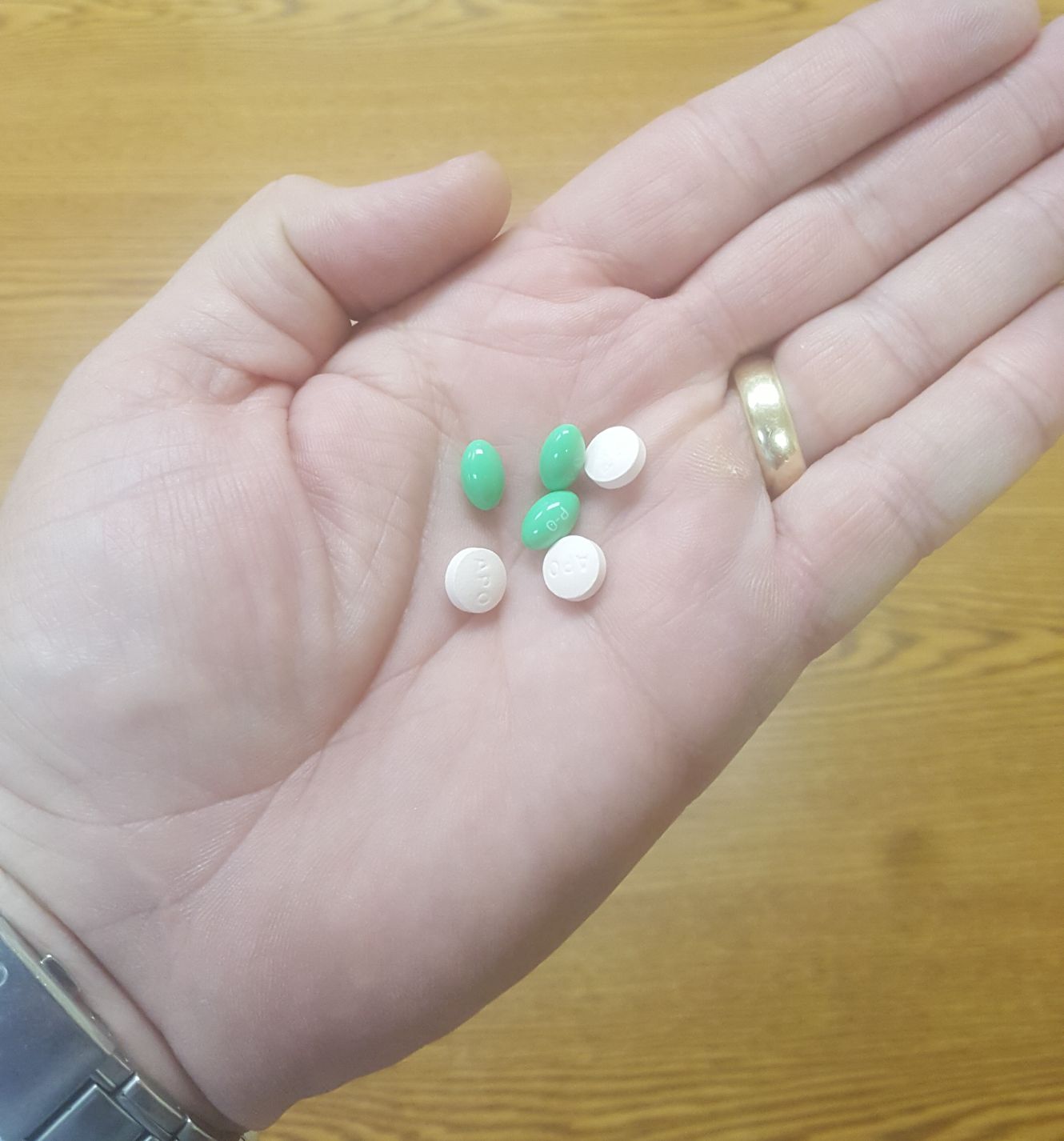

- They’re giving patients non-opiate medications such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, aspirin, muscle relaxers such as Baclofen, local anesthetics, and naproxen. If it’s appropriate, some patients are treated for pain with anticonvulsants such as Lyrica or Neurontin or with selected antidepressants such as Cymbalta or Pamelor.

- They’re focusing not just on proper anesthesia and pain treatment during surgical procedures, but on a patient’s post-surgery pain through what’s known as Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. It calls for a multidisciplinary team of providers to adopt a culture of reducing a patient’s stress response to surgery as a way to help the patient recover more quickly. “Part of this is having realistic expectations on pain,” Gusa said. “Patients should expect pain after surgery.”

- They’re getting on the same page with fellow providers across the Medical Center, from family medicine to surgery to UMMC’s smoking cessation program.

- Patients are encouraged to take advantage of the Medical Center’s new Center for Integrative Medicine. Its caregivers work with chronic pain patients on lifestyle modifications related to diet, exercise, vitamins and physical therapy, said Stacey Kitchens, a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner and the center’s associate director.

- In the School of Medicine, physicians will teach students how to manage pain as a key part of their education. “We’re bringing together clinicians and scientists to come up with a curriculum on pain management and assessment, pain expectations and psychology,” Oswalt said.

UMMC takes a team approach to managing patients’ acute or chronic pain that brings in physicians, psychologists, nurses trained in pain management, and other support staff at the Pain Management Center. Services for acute pain might include epidural analgesia, nerve blocks, local anesthetics and anti-inflammatory drugs in addition to opioids.

Staff also might work with patients using biofeedback, a non-drug method of self-regulating behavior to manage acute and chronic pain, especially in headache or migraine sufferers. Patients learn to control functions such as breathing and heart rate and to take steps to ward off looming pain with relaxation or stress management in addition to medication.

Caregivers in the Department of Psychiatry do not directly treat or prescribe medications to patients for their pain but have conversations about addiction.

When patients come to the outpatient psychiatry department, the prescription monitoring program is reviewed, said Dr. Mark Ladner, associate professor of psychiatry. “We review to see if there are any patterns consistent with abuse of medication and addiction,” he said. “Many patients may be embarrassed to start a conversation about addiction, and this is one way to start a conversation.”

Patients with stressful life issues can have more difficulty dealing with addiction and with coping with the changes needed to taper off opioids, Ladner said. Their perception of pain can be affected by their psychological state of mind and problems such as depression and anxiety, he said.

“We can treat the depression and anxiety, and this may improve the patient’s ability to cope with pain,” he said. “Some anti-depressant medications can help alleviate pain. If someone has depression and pain, then we might choose a medication like duloxetine that can treat both depression and pain.”

Bacon wants to educate physicians who are discharging surgery patients from the hospital on the appropriate amount, strength and duration of opioids that they’ll need at home. The goal is to manage their pain so that post-surgery complications can be minimized, and so that their pain doesn’t spiral out of control, possibly leading to re-hospitalization.

“Seven percent of surgical patients who have never been on a narcotic before then will be on it 12 months after surgery,” Bacon said. “That’s a staggering number. And, the opioid-tolerant patient coming in for surgery is one of the hardest to deal with.”

Oswald said that physicians need to do a better job of explaining to some patients that they might never be totally pain-free, but that a ready bottle of opioids will do them no favors, in the long run.

“Realistically, you can be pain-free and dead, or you can have pain and be breathing,” Oswalt said.