Image above: Grand Coulee Dam (Image courtesy of U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation – Creator: Kirsten Strough)

Humans have been harnessing the power of water to perform work for thousands of years. The Greeks used water wheels for grinding wheat into flour more than 2,000 years ago, while the Egyptians used Archimedes water screws for irrigation during the third century B.C. China developed trip hammers powered by water wheels in the second century B.C. However, the evolution of the modern hydropower turbine began in the mid-1700s when a French hydraulic and military engineer wrote the groundbreaking Architecture Hydraulique. Since then, more innovations in turbine technology came about with the Francis turbine, the Pelton wheel and the Kaplan turbine.

Across the U.S. in the 1880’s and 1890’s, small hydropower plants were popping up around the country to power mills and light some local buildings. Some of the first commercial hydroelectric installations were the Redlands Power Plant in California in 1893 and the Edward Dean Adams Power Plant built in 1895 at Niagara Falls. Soon after 1900, advances in hydropower facility designs and major policy initiatives, such as the New Deal and creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority, led to the construction of major projects like the Hoover and Grand Coulee dams. Hydropower accounted for 40% of the nation’s electricity generation by 1940.

Hydropower was seen as one of the best ways to meet growing energy demand and was often tied to the development of energy-intensive industries such as aluminum smelters and steelworks. However, financial constraints and concerns about the environmental and social impacts of hydropower development halted many projects at the end of the last century.

Some countries are now reassessing hydropower’s value and role in national and economic development. Existing practices have been pushed aside with new hydropower developments putting a greater focus on sustainability and affected communities. This shift resulted in a growing appreciation of hydropower’s role in combatting greenhouse gas emissions, reducing poverty and boosting prosperity – particularly in Asia and South America. Between 2000 and 2017, nearly 500,000 megawatts (MW) in hydropower capacity were added worldwide. Overall global hydropower installed capacity reached 1,330,000 MW in 2020.

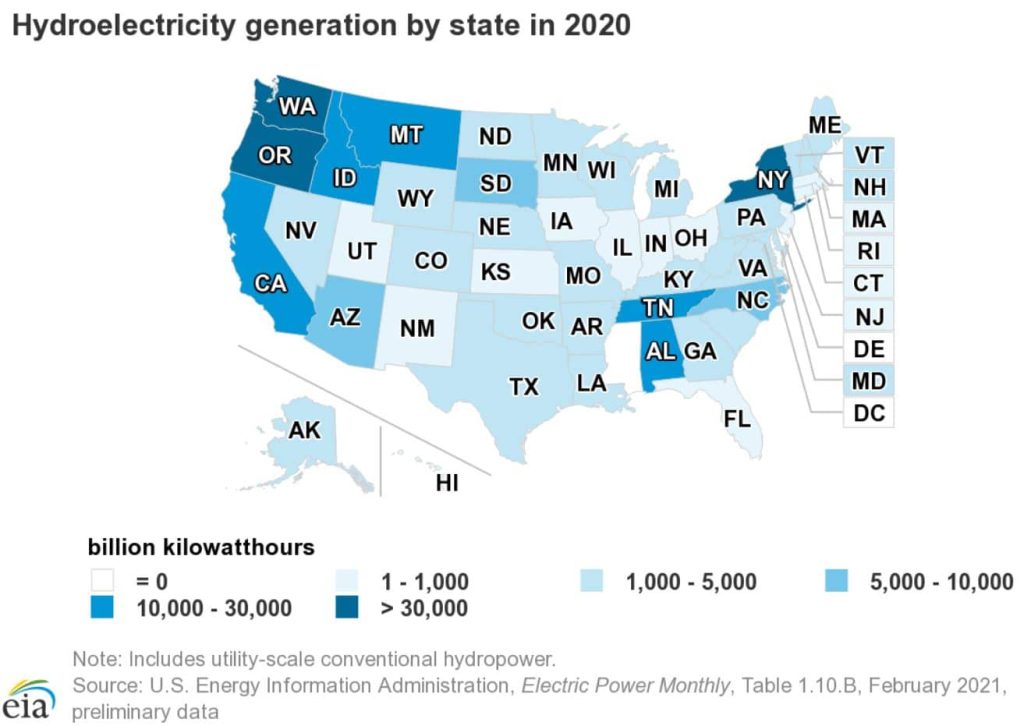

The United States currently has 102,840 MW of hydroelectric generation capacity consisting of 79,946 MW of conventional hydroelectricity and 22,894 MW of pumped-storage hydroelectric generating capacity. Five states, including Alabama, make up 51% of hydroelectric generation capacity. Precipitation levels can have an impact on annual generation so capacity does not always reflect performance. Five states, including Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia, account for 61% of U.S. pump-storage hydroelectric capacity.

Still, hydroelectric generation capacity could be so much more. There are nearly 90,000 dams in the U.S. Only a small fraction (3%) generate power. The potential hydropower production from these existing impoundments could achieve 12,000 MW.

While there are conventional hydropower/hydroelectric facilities that are in nearly every state, one state sticks out as having zero generation from hydroelectric resources – Mississippi. Despite being surrounded by rivers (the Mississippi and the Tennessee-Tombigbee) and ocean (Gulf of Mexico) and having hundreds of miles of rivers and streams throughout the interior of the state, Mississippi has not facilitated the development of these types of projects. However, that could be changing very soon!

Rye Development in conjunction with a funding partner is a developer of 22 run-of-river hydropower projects and holds 13 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) licenses on existing dams in six states, including four FERC licenses in Mississippi. These projects are located in the Yazoo River Basin on the four flood control dams owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The lakes are the Arkabutla, Enid, Grenada and Sardis. Ranging in capacity from 4.6 MW to 14.6 MW with a total capacity of 33.3 MW, the annual expected generation of 119,400 MWh will provide a valuable addition to the state’s generation mix and can power up to 11,000 homes. Building these projects will create 150+ jobs and cost approximately $80 million. With an expected lifespan of 80 years, these projects can contribute to the local economies for several generations.

Rye has also proposed constructing a hydropower facility at the Ross Barnett Reservoir near the Spillway. Analysis indicates that three 7-MW Kaplan turbines could generate 50,000 MWh annually. Three 14-foot diameter penstocks could be tunneled through the existing dam. This is a preliminary assessment and much work would need to be done to bring this to fruition.

Does hydropower have a future in Mississippi? Time will tell. I know that I am excited about the opportunities for hydropower technology, whether it is run-of-river, wave power, tidal power, pumped-storage or other. I wish Rye Development and other innovators the best as they bring new clean energy resources to market.