The year was 2008. I remember it vividly. Senator Barack Obama, candidate for president of the United States, was discussing his plans for health care reform in a television ad. He talked about his plan for employer “shared responsibility.”

I generally didn’t pay much attention to politics or political candidates in those days. I always felt that if the government just left me alone, our business would thrive, and my personal life would be largely unaffected. But hearing the word “employer” in the ad, got my attention. I felt compelled to dig into the details of Mr. Obama’s plan for health care reform, which was published on his campaign website.

Barack Obama’s “shared responsibility”

That’s where I found a sketchy description of “shared responsibility” from an employer’s perspective. Mr. Obama’s plan would impose a federal mandate on large employers, defined as those with 50 or more employees, to cover a significant portion of health insurance premiums for their employees. Recruiting staff is a continuous and challenging task for employers. To satisfy their personnel needs, companies must offer competitive compensation packages, including benefits, chief of which is health insurance. Our company was no exception, especially considering that the demand for human talent in the technology industry has outstripped supply for, well, as long as the industry has existed.

So, while our wages and benefits were competitive, as dictated by dynamic market conditions, Mr. Obama’s shared responsibility would increase our monthly costs by nearly $20,000 – with fewer than 100 employees at the time. This increase was primarily driven by candidate Obama’s plan to require that employers cover most of the premium cost of all coverage categories – not just the employee – but the employee plus their dependents, including the employee’s spouse.

The plan structure, still in effect today in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), mandates that large employers provide “affordable” coverage, where the employee’s cost of premiums would not exceed a specified percentage of their household income. But wait, that would mean an employer would have to ascertain the income of an employee’s spouse to determine compliance with the affordability requirement. Additionally, in the case where both spouses worked, which employer would be responsible for providing “affordable” coverage? Would they split the cost of “shared responsibility”? These are complex questions that came to mind in 2008, just from reviewing a presidential candidate’s proposal.

So, for answers to these thorny questions, I did what any rational business owner would do: I called our company’s labor lawyer. I remember the telephone conversation like it took place yesterday. I was firing various nuanced questions at our trusted counsel, hoping he could offer enlightening answers. But his response was totally understandable. He advised that my concerns were quite premature, that there was no guarantee that Barack Obama would be elected or that his vision for health care reform would be shaped into a bill, that the bill would pass, and that the courts would uphold it. He also explained that any bill enacted into law would require codification, and the final code would address my specific concerns. But codification wouldn’t occur for some period after the enactment of any health care reform legislation.

While I appreciated our attorney’s honest and forthcoming response, I remained concerned about how the impact of such sweeping mandates would affect our business. I’ve steadfastly believed that faith, confidence, and certainty drive business investment, risk-taking, and hiring. Absent some degree of clarity about the future, business owners – particularly small and mid-sized businesses – become risk averse and tend to hunker down.

Scaling our business, both by expanding our geographic footprint and broadening our solutions portfolio, involved financial risk, including adding expensive staff.

The prospect of a substantial increase in monthly expenses should Mr. Obama’s “shared responsibility” mandate become law, factored into our business decisions. With no clear understanding of how Mr. Obama’s reforms would impact our bottom line, we treaded lightly before making any long-term financial commitments.

The stress induced by employer “shared responsibility” motivated me to pay closer attention to public policy, lawmaking, and government-imposed regulations. “Those politicians and bureaucrats are serious about making life difficult for business,” I said to myself.

My frustration with being unable to gain clarity on the future of such a pivotal issue to our business was the catalyst for my sudden obsession with public policy, in particular health care policy, which was garnering all the attention in Washington at the time. I began to consume and collect all the information I could find concerning our convoluted and complex health care economy (HCE). I reviewed countless articles, analyses, and white papers on health care reform.

In July 2009, the first bill to accomplish President Obama’s legislative priority of reforming health care in this country was introduced in the House. America’s Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009 (H.R. 3200), as it was styled, didn’t pass the chamber in which it originated (fortunately) but it incorporated the vaunted employer “shared responsibility” as Mr. Obama proposed during his campaign.

I scanned/read most of the 2,454-page monstrosity over the course of a few weeks. No easy task, as there are countless references to existing code, most notably the IRS Code of 1986. So full comprehension of the bill required digging into at least some of the more than 6,000 pages of federal tax regulations.

The Affordable Care Act becomes law

In September 2009, the House introduced the Service Members Home Ownership Act of 2009, authored by Rep. Charles Rangel (D-NY). It passed the House in November 2009 and passed the Senate with significant amendments as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (ACA), commonly known as Obamacare, on December 24, 2009. The House agreed to the Senate amendments on March 21, 2010 (219-212). President Obama signed the ACA into law two days later.

The ACA included most of the original provisions championed by candidate Barack Obama on the campaign trail. One noticeably absent provision was the public option. The public option would establish a government insurance program that would compete with private health care insurers. Democrats for years have sought to fully replace private health insurance with government-provided coverage, sometimes referred to as “Medicare for All.”

Once enacted, countless articles, reports, and white papers were published about the 906-page monstrosity about which Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi infamously quipped, “We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what is in it, away from the fog of the controversy.” Emanating from the actual bill are over 20,000 pages of regulations. That’s the “codification” of which our attorney advised.

Many of those regulations were added to the IRS income code. In fact, much of the law is just a series of debits (subsidies, expansion of government benefits, such as Medicaid expansion) and credits (a slew of new taxes). The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) is my go-to document concerning the tax provisions incorporated in the ACA. It weighs in at a mere 164 pages. That’s a lot of pages to summarize just the tax provisions of a law focused on health care.

The ACA incorporated 21 new federal income tax provisions, of which 14 were new taxes. The new taxes included an individual mandate to buy health insurance, a tax on businesses with over 50 full-time employees who do not provide affordable coverage, a 10% tax on indoor tanning services, a net income investment income tax of 3.8% on investment income, a 0.9% increase in the Medicare Part A tax for high-income earners and numerous others. Since its enactment in 2010, many of the ACA’s taxes have been repealed, such as the individual mandate tax, the tax on medical device makers, insurers, pharmaceutical makers, and the medicine cabinet tax.

You would be hard-pressed to identify any federal tax and spending bills that once implemented, generate the revenues planned and limit spending to the costs as budgeted. For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the indoor tanning tax would generate $2.7 billion in revenue from 2010 to 2018. Actual revenue generated over that period was roughly $680 million. Oops…

The overarching goal of the ACA was to achieve universal coverage – where everyone in the country would have health insurance. The goal of universal coverage is a worthy pursuit. Imagine a society where all health care services were compensated. Not only would health outcomes improve, but the cost of uninsured care, estimated at $35 billion annually, would be largely eliminated.

To support this goal, the ACA included an array of provisions on the debit (spending) side of the ledger:

- Individual Insurance Marketplaces – online systems, often referred to as “exchanges,” where consumers can shop for and enroll in health plans and receive income-based federal subsidies toward premium costs.

- Medicaid Expansion – Allowing states to make benefits available to able-bodied adults earning less than 138% of the federal poverty level.

- Small Business Insurance Marketplaces (SHOP) – online exchanges where firms with 50 or fewer employees can obtain subsidized coverage for their personnel.

In addition to the financial provisions of the ACA, the sweeping law also included several popular, but costly, insurance reforms – again designed to facilitate and maintain universal coverage while reducing consumer costs:

- Health insurers cannot deny people coverage or charge substantially more if they have a preexisting health condition.

- Insurers cannot offer plans that include annual or lifetime dollar caps on essential health benefits.

- Annual out-of-pocket costs, including deductibles, co-pays, and co-insurance are limited.

Thirteen years since the ACA’s enactment, it’s clear that President Obama’s promise that the law would reduce average premium costs by $2,500 a year never materialized. Conversely, premiums have steadily risen since the ACA was passed. It is reasonable to attribute rising health insurance costs to the law’s major insurance reforms listed above.

The ACA’s plan to achieve universal coverage

So, while it is hard to deny that the concept of universal coverage has value, the fundamental question is, how best to achieve this goal – one that has been historically elusive.

The goal of the ACA was to cover every American in one of six broad categories of health insurance. The law’s individual and employer mandates combined with regulatory reforms, enhancements to Medicaid, and creation of subsidized marketplaces would facilitate full, universal coverage. The following chart shows the distribution of coverage by insurance category of the total U.S. population (shown in millions), in 2010 before the ACA was passed and as of 2022, along with the law’s impact on each category.

| Category | 2010 | 2022 | ACA’s Impact |

| Medicare | 34.3

11.4% |

47.2

14.4% |

New taxes to increase funding |

| Medicaid | 51.0

17.0% |

72.0

21.8% |

Added eligibility of able-bodied adults (Medicaid Expansion) |

| Military | 4.5

1.5% |

4.2

1.4% |

|

| Employer Group) | 148.0

49.2% |

159.0

48.7% |

Large employers – mandate to provide affordable coverage; small employers – SHOP exchanges |

| Individual (Non-Group) | 15.8

5.3% |

21.0

6.3% |

Creation of online marketplaces for subsidized coverage |

| Uninsured | 47.0

15.6% |

26.0

7.8% |

|

| Total | 301.0

100.0% |

330.0

100.0% |

Here’s the same data set for the State of Mississippi:

| Category | 2010 | 2022 |

| Medicare | .33

11.5% |

.42

14.6% |

| Medicaid | .68

21.5% |

.75

24.1% |

| Military | .05

1.9% |

.05

1.4% |

| Employer Group) | 1.1

40.4% |

1.2

42.5% |

| Individual (Non-Group) | .12

4.5% |

.18

6.4% |

| Uninsured | .51

18.1% |

.30

10.9% |

| Total | 2.87

100.0% |

2.85

100.0% |

Medicaid, defined

Medicaid is a government health insurance program that provides free or low-cost coverage to certain low-income people. Enacted in 1965 as an amendment to the Social Security Act of 1935, the program is jointly funded by the federal government and states and administered by the states in accordance with federal guidelines.

Federal funding to the states for their Medicaid programs is known as the federal medical assistance percentage, or FMAP. The FMAP is determined using a formula based on the average per capita income for each state, at no less than 50% by law. Having the lowest per capita income of the 50 states, Mississippi’s FMAP is the highest at 76.9%. The state’s 23.1% share is appropriated annually by the Legislature.

The total annual all-in cost of the Medicaid program in Mississippi is just over $6.2 billion, with the federal government contributing over $5 billion which funds the bulk of the program’s cost, consistent with FMAP. The state’s portion is approximately $1 billion annually, consuming roughly 19% of total General Fund expenditures, the second most costly budgetary line item behind education.

The federal Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) indicates that in March 2023, the national Medicaid rolls swelled to an enrollment of roughly 93 million, due to the continuous enrollment provision of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) signed into law by President Donald Trump in March 2020. That’s a jaw-dropping 1 in 4 Americans in free, government-sponsored health insurance. The continuous enrollment provision barred states from removing anyone enrolled in Medicaid at the time the law was passed, or anyone enrolled after – even if they were no longer eligible for benefits, e.g., their income was too high to qualify for Medicaid coverage.

In Mississippi, the Medicaid rolls have risen to over 850,000 under the FFCRA’s continuous enrollment provision, or roughly 30% of the state’s total population.

To offset the additional costs to states associated with continuous enrollment, the federal government increased its share of Medicaid costs by 6.2%. The continuous enrollment provision and the enhanced FMAP remained in place until March 2023, consistent with the permanent expiration of the national public health emergency declared by Trump in March 2020.

Concurrent with states unwinding their Medicaid rolls beginning this past March, the federal government has been phasing down the 6.2% FMAP increase, incrementally, until fully eliminated by December 31, 2023.

Until the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, Medicaid insured the following covered groups based on income and other criteria:

- Children

- Pregnant women

- Elderly

- Parents/Caretakers of minor children

- People with disabilities

The ACA included a provision to extend Medicaid coverage to able-bodied adults whose income is at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), commonly known as “Medicaid expansion.”

Shortly after the ACA was passed, 26 states, the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), and individual plaintiffs Kaj Ahburg and Mary Brown sued to overturn the law. The plaintiffs asserted that the law’s individual mandate and Medicaid expansion were unconstitutional. In a 5-4 ruling decided on June 28, 2012, the Supreme Court upheld the law’s individual mandate, but ruled that the federal government cannot mandate that states expand Medicaid coverage to able-bodied adults, pursuant to the ACA, as a condition of receiving federal funding for existing Medicaid programs.

Had SCOTUS upheld that requirement, all 50 states would have been compelled to expand Medicaid. Since the program became available in 2014, 40 states have expanded. Mississippi is one of 10 states that has not.

The arguments for and against Medicaid expansion

Virtually any discussion concerning the plight of health care in Mississippi always includes, if not fully revolves around, Medicaid expansion. The case could be made that the issue of expansion was the pivotal deciding factor in both the Republican gubernatorial primary won by Governor Tate Reeves over challenger Justice Bill Waller in 2019 and the 2023 general election which pitted incumbent Governor Reeves against Democrat populist challenger Brandon Presley.

The funding model for the expansion group (able-bodied adults) is different than traditional Medicaid. As an incentive to adopt expansion, the federal government paid 100% of the cost of coverage from 2014 to 2016, then reduced the fed’s share beginning in 2017 settling at 90% for 2020 and subsequent years.

In essence, Medicaid expansion has been a political hot potato in Mississippi for over a decade. Proponents assert that expansion is necessary to ensure viability of the state’s rural hospitals – hit particularly hard by the uninsured. Supporters argue that expansion would create jobs, infuse nearly a billion dollars of federal funds into Mississippi, reduce the state’s cost of the existing Medicaid program, and improve access to health care and health outcomes.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about expanding Medicaid in Mississippi. Cost to the state tops that list of concerns. Most estimates peg Mississippi taxpayers’ cost for Medicaid expansion at $100 million to $200 million annually. While the federal government currently covers 90% of the cost of care for expansion enrollees, opponents fret over the financial consequences to Mississippi of any future downward adjustment to the federal reimbursement rate. To be fair, that’s highly unlikely, given that 40 states have expanded. Of course, the federal government could also reduce the FMAP for traditional Medicaid which would severely upend the state’s budget. Again, not a likely scenario.

While reform of the federal reimbursement model is always a possibility, such action would require a political environment and congressional sentiment in Washington less likely than the production of a $3 bill. Additionally, Mississippi’s hospitals have expressed willingness to cover the state’s cost of expansion. In this scenario, Medicaid would be technically expanded by adding a new coverage group at no cost to state taxpayers. From an economic perspective, this is akin to the Medicaid reimbursement reforms proposed by Governor Reeves in September 2023 and recently approved by federal CMS. The recently approved reforms will drive nearly $700 million in additional FMAP reimbursement to Mississippi’s Medicaid providers. Hospitals will cover the state’s ~25% share.

Medicaid reimburses generally below covered service cost; thus, losses are incurred when care is rendered to Medicaid patients. Extending Medicaid coverage to more Mississippians would rack up more losses, say opponents. This is tough to measure, without accurate data calculating the cost of uncompensated care to those who would qualify for Medicaid with expansion. Perhaps some reimbursement – even at an amount under cost – is better than zero payment for services. But that could be marginally offset by a loss or reduction of Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payments (DSH) from the federal government and a possible increase in service delivery with more people being covered under expansion. A financial modeling exercise worth completing, for sure.

Expansion opponents express skepticism that boosting the rolls of Medicaid would produce better health outcomes. This, too, is highly subjective and difficult to measure. This objection gives rise to several questions: Would the current supply of care be insufficient to accommodate low-income, able-bodied working adults who would be added to Medicaid? Would Mississippi experience an increase in the supply of care? Would our anti-free market Certificate of Need (CON) laws hinder expansion and creation of new health care facilities and services as potentially needed with expansion? Are the 300,000 uninsured Mississippians currently receiving no health care? If that were the case, providers/hospitals would report no costs associated with uninsured care in their financial statements. If the uninsured were able to enroll in private coverage, would the state’s health care system be able to handle the possible increase in the demand for care?

With respect to health outcomes not improving under Medicaid expansion, does that indicate that the quality of care when Medicaid is the payer is inferior to care when commercial carriers or Medicare is paying the bill? If adding a coverage group to Medicaid, as expansion would do, drives negative outcomes, should the state abandon traditional Medicaid?

Another reasonable concern expressed by expansion adversaries is that those eligible for Medicaid coverage under expansion but who are currently enrolled in their employer’s group coverage would terminate their employer-provided plan, and sign up for Medicaid, since their premium cost would be zero. It’s difficult to calculate how many would drop their employer-provided commercial coverage in Mississippi for Medicaid. The losers in this scenario would be providers, whose reimbursement would decrease when Medicaid is the payer as compared to commercial reimbursement.

Supporters of Medicaid expansion, including 2023 Democrat gubernatorial candidate Brandon Presley, maintain that expansion is necessary to ensure the long-term viability of Mississippi’s hospitals, particularly in the rural areas of Mississippi.

To summarize, Medicaid expansion advocates say adding a coverage group to Mississippi’s Medicaid program will “save” the state’s hospitals, and expansion opponents say the health care situation in the Magnolia State will worsen. As is the case with nearly all complex, contentious policy matters, the truth likely lies somewhere in the middle.

California, with a population 13 times that of Mississippi, is experiencing a health care crisis. According to health care management consulting firm Kaufman Hall, one in five hospitals in the Golden State is at risk of closure. Over half of the state’s 400 hospitals are losing money. In 2022, California hospitals lost $8.5 billion. California was one of the first states to expand Medicaid when the option took effect in 2014.

The renowned Cleveland Clinic, a nonprofit that operates 21 hospitals, reported a $1.2 billion net loss in 2022, with non-operating losses totaling $1 billion. The system returned to profitability for the first three quarters of 2023, but huge swings illustrate the ongoing volatility in the hospital industry – whether located in rural or urban settings.

A useful and instructive exercise would be for several of the state’s hospitals to recast their last three years’ financial statements with the assumption that Medicaid was expanded during that period. Granted, this would be a difficult undertaking because it would require identifying all patients served during the period who would have qualified for Medicaid coverage under expansion. Presumably, the hypothetical income statements would reflect an increase in revenue from Medicaid and a decrease in the value of uncompensated care. Additionally, the task of creating these “what-if” financial scenarios would also require a downward adjustment to DSH payments associated with uninsured care, as applicable.

Would the resulting modified prior year financials present a positive impact on the bottom line of hospitals analyzed, as proclaimed by Medicaid expansion advocates or would the impact be immeasurable as asserted by expansion opponents?

Achieving universal coverage without expanding Medicaid

Implement a free market in health care

As a conservative, I agree that the best approach to solving virtually all societal problems involves more free market principles, individual responsibility, and less government. Liberals assert that health care is a right, and therefore, the government should implement whatever measures are necessary to ensure all Americans, regardless of financial status and other circumstances, receive the care they need. Health care is a commodity produced by and delivered by humans. Nobody is entitled to the work product of others without fair remuneration to the work product’s producer.

But that’s exactly the system that exists today in the provision of health care in the United States. The Emergency Medical Treatment Act (EMTALA) was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. The sweeping legislation requires that hospitals that participate in Medicare (the vast majority) and offer emergency services must administer medical screening examination (MSE) and stabilize patients experiencing an emergency medical condition (EMC), regardless of an individual’s ability to pay. I’m not aware of any other industries that are compelled by law to provide products and services at no charge.

If EMTALA remains the law of the land, which in effect forces hospitals to deliver “free” service, a robust free market in health care is not attainable. It’s highly unlikely that EMTALA will ever be repealed. To be fair, the federal government does provide some reimbursement for uncompensated care, mostly from the Medicaid DSH payments, but the amount falls far short of the actual cost incurred in the provision of “free” care.

To bolster the free market in health care, Mississippi lawmakers should repeal the state’s Certificate of Need laws. Mississippi’s CON statutes empower the Mississippi State Department of Health to approve, control, and regulate health care assets and resources in the state. As one of 35 states with CON laws, the framework essentially amounts to central planning of the supply of care. Opponents of CON laws assert that patients and taxpayers are harmed by having access to fewer health care options and experiencing higher overall health care costs. Imagine if Wendy’s had to obtain permission from McDonald’s to open a restaurant. That’s the functional equivalent of Mississippi’s CON statutes.

Opponents of repealing the state’s CON framework express concerns that allowing more competition would inflict more financial pressure on the state’s existing hospitals, already under tremendous economic strain. They warn that new health care facilities that would sprout up upon repeal would siphon commercially insured patients leaving existing full-service hospitals to service patients covered by lower-reimbursing Medicare and Medicaid or the non-paying uninsured.

It’s difficult to predict how the repeal of CON would positively affect the health care ecosystem in Mississippi. Would repeal drive capital investment in new health care resources, especially hospitals, and facilitate the expansion of existing institutions, especially in underserved rural regions of the state?

Or is the business risk too high, with the state’s outsized unhealthy population and negative payor mix? In my view, regardless of the perceived risks, the market – not government – is the best arbiter of supply and demand – regardless of commodity.

Drive down the cost of premiums by allowing health insurance to be sold across state lines

This is an often-heard suggestion to drive the cost of health insurance down by increasing competition among carriers who sell health insurance. Under the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, insurance is regulated at the state level. Thus, companies that sell insurance must be licensed by the state entities that regulate the insurance industry in each state, such as the Mississippi Insurance Department. Companies that wish to sell insurance in Mississippi can do so by simply obtaining the required license.

The big hurdle for a health insurer to operate profitably in any state is to establish a robust network of health care providers that will accept the carrier’s coverage. People want to pay minimum out-of-pocket when health care services are rendered. If the provider is a member of their insurance carrier’s network, they will file a claim on behalf of the patient, billing the patient’s carrier for the cost of services provided – notwithstanding deductibles, co-pays, and co-insurance.

Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) also generally negotiate lower costs for services from providers that belong to a plan’s network. Subscribers also want coverage accepted by a wide range of practitioners, including primary care, specialists, and hospitals.

It’s difficult for new carriers to establish a provider network in a state in which they have no current presence. First, building a network from the ground up is a significant and risky investment. Second, most providers prefer to deal with as few carriers as possible. Providers and carriers are constantly squabbling about coverage for claims submitted and pre-approval for services. Adding more to their payer mix is a costly endeavor.

Then there’s the financial reality of the health insurance industry’s operating model. Consumers see the cost of premiums constantly increasing, so naturally, they believe that health insurance companies are producing outsized profits, thus driving up the cost of care. The truth is that the health insurance industry is not highly profitable, especially relative to other industries.

Health insurer profit is effectively limited by federal law. A key provision of the ACA requires insurers to pay 80% of their premium revenue in claims. Known as the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR), insurers are required by the ACA to issue payments to their insured customers on an annual basis to account for any MLR experience under the 80% threshold. Nearly $12 billion in MLR rebates has been paid out by the industry since the provision became effective in 2012.

The top 5 insurers, which account for 80% of the commercial market, produced roughly $42 billion in net profit for 2022. Two of those companies produced net losses during 2022. The entire value of health care expenditures (HCE) for 2022 was $4.5 trillion, or $13,493 per person, and accounted for 17.3% of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

For perspective, Apple Computer, Inc. is on track to produce ~$120 billion of net income in the current fiscal year – 3 times the total net profit produced by the entire health insurance industry. I don’t share this data to defend insurers, but rather to simply illustrate the financial math that should underpin proposals to address the uninsured challenge.

The aggregate net profit of the health insurance industry is approximately 1% of total health care expenditures. If all the profit produced by the industry was eliminated, such that insurers were transitioned to not-for-profit operators by reducing the cost of premiums, savings to consumers would be roughly 3% of premium cost. That still puts the cost of premiums out of reach for most of the nation’s low-income population.

The average annual price of health insurance premiums for 2023 was $8,435 for single coverage and $23,968 for family coverage. Industry analysts project a 7% increase in premiums for 2024. The MLR will still apply.

To boost their bottom lines, many insurers provide third-party administration (TPA) services for self-funded plans or for carriers based in other states who have covered employees in the TPA’s state. Many of the nation’s largest insurers have also acquired Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBM) to diversify and supplement their core health insurance business. This vertical integration is a key driver of the upward trend in health care costs. Oh, those unintended consequences of big government central planning socialism.

Hospitals shoul reconfigure their operating model to boost efficiencies

There is little doubt that most of the state’s hospitals, and most of the nation’s for that matter, were built to accommodate treatment approaches utilized during the era they were created. Driven by innovations in surgical procedures, drugs, therapies, treatments, and the practice of medicine in general, many operations and treatment regimens that once required a prolonged stay in the hospital post-surgery can now be done on an outpatient basis or require much shorter stays. The fixed (and some variable) costs associated with operating aging hospitals are indeed having a deleterious impact on these institutions’ bottom lines.

The misalignment of aging hospital operating models with the practice of modern medicine is widely perceived as the root, if not exclusive, cause of negative hospital cash flow. Additionally, the financial challenges currently plaguing the state’s hospitals are widely believed to only affect rural facilities. Many of Mississippi’s hospitals serving the state’s urban areas are also either cash-flow negative or barely in the black.

As a result, many suggest that simply improving operational efficiency will stabilize the financial condition of the state’s hospital network. For sure, every organization, whether public or private, should continuously seek to root out extraneous costs and streamline their operating environment. However, I submit that no amount of retooling, reconfiguring, repurposing, reorganizing, reengineering, or reimagining a business entity (yes, hospitals are businesses) can mitigate and offset the costs associated with the involuntary provision of free service. No business entity builds a viable business model around “free” service – unless paying customers (patients, in health care) are picking up the tab for those not paying for service.

Allow companies to add non-employees to their group health care plans

I know this sounds radical. This idea first occurred to me when my wife Julie and I served as foster parents for two local minors who tragically lost their single mother and had no other family member available to take them into their home. In accordance with law, foster children are enrolled in Medicaid. I petitioned the Mississippi Department of Human Services (MDHS), which oversees the foster care program, to allow the children to be added to my company’s group plan. I offered to absorb the additional cost of adding the two brothers to my private plan. Unfortunately, department officials rejected my request, citing law that requires foster children to be enrolled in Medicaid.

But what if companies could “adopt” truly needy, uninsured, non-employees onto their group plans at no cost to the covered individual or family, as a simple act of generosity? The state could provide at least a reasonable tax credit to offset costs. Insurers would also approve such a program, as only employees are eligible for a business’ group health care programs. I’m confident that we would see broad participation in such a program by the private sector in our state. Indeed, there are numerous details to flesh out to make this idea a reality, but it’s worth exploring.

Encourage the uninsured to enroll in subsidized coverage offered in the ACA marketplaces

This idea is really a proverbial no-brainer. It’s perplexing that we haven’t seen a rush of the uninsured to the marketplaces to obtain coverage since the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) was enacted on March 11, 2021. What does ARPA have to do with health insurance? Let’s explore.

A key provision of the Affordable Care Act, enacted in 2010, was the creation of online Health Insurance Marketplaces, also known as “exchanges,” where individuals can obtain coverage during an annual open enrollment period. The premise of the exchanges is to provide health insurance options to those who do not have access to employer-provided coverage or who do not qualify for public insurance, e.g., Medicare and Medicaid.

Financial assistance is also available in the form of premium tax credits for health insurance purchased in the Health Insurance Marketplaces to those whose employer does not offer affordable or sufficient coverage. Employer-sponsored plans are considered unaffordable when the employee’s cost of contributions for the company’s coverage exceeds 9.83% of the employee’s household income.

Plans that cover at least 60% of total average costs for covered benefits a plan insures (also known as actuarial value) are deemed sufficient, or in compliance with the minimum essential coverage as required by the ACA.

Note that these employer-shared responsibility provisions do not apply to employers with fewer than 50 full-time employees, but rather are part of the shared responsibility for applicable large employers (ALE). Failure to meet the ACA’s shared responsibility provisions triggers employer shared responsibility payments to the IRS.

As stated earlier, the marketplace premium tax credits (subsidies), are income-based, tied to the federal poverty level guidelines. Premiums are calculated as a percentage of household income (HHI), where those with lower incomes pay a lower percentage of their HHI for coverage and those with higher incomes pay a higher percentage of their aggregate income for premiums.

Most Americans are familiar with the chief provisions of the $1.9 trillion ARPA, consisting of a series of economic stimuli designed to hasten the nation’s recovery from the negative economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Key elements included expanded unemployment benefits, direct payments to individuals, enhanced tax credits, aid to state and local governments, funding for education and housing, and healthcare-related funding.

Receiving less attention were two significant reforms to the ACA marketplaces included in the ARPA:

- Restructuring the subsidy model to lower the cost of premiums, especially for low-income subscribers.

- Removing the “subsidy cliff,” allowing those with incomes that exceed 400% of the federal poverty level to purchase subsidized coverage.

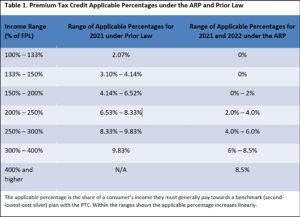

Point one is of significant relevance to Mississippi, as an alternative to Medicaid expansion to insure the working poor in our state. The chart below tells the story. The leftmost column displays income ranges as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). Column 2 specifies premium costs for a benchmark middle-tier (silver) plan expressed as a percentage of household income before the passing of the ARPA in March 2021. The third column shows the percentages applied to household income to calculate premium costs after the ARPA was passed.

For example, an individual with an annual household income of 150% of the federal poverty level, or $19,320 would pay 4.14% of household income, or $800/year for a silver plan.

With the more generous subsidy structure implemented in the ARPA, premium costs for the same individual with an HHI of 150% of the FPL would incur an annual premium cost of $0.00 for the same silver policy.

It works out that ARPA subsidy enhancements are more generous than Medicaid expansion for the group that expansion would cover – low-income, able-bodied adults. Whereas Medicaid expansion would make coverage available at no cost to those whose income is at or below 138% of the federal poverty level, zero-cost premium commercial coverage is available (today) in the ACA marketplaces for incomes up to 150% of the FPL.

In general, out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, co-insurance, co-pays) for Medicaid coverage are low or near zero. Contrast that to commercial coverage, such as plans sold in the exchanges, where annual out-of-pocket (OOP) costs are limited to $9,450 for individual coverage and $18,900 for family coverage for 2024.

However, depending on income, enrollees in marketplace plans are eligible for financial assistance to offset OOP costs. Known as Cost Sharing Reductions (CSR), the maximum out-of-pocket costs for those whose income is between 100 and 150 percent of the FPL who purchase a CSR-eligible silver plan is $3,150 for individual coverage and $6,300 for family coverage.

While the CSR feature of the marketplace plans drives down OOP costs relative to coverage purchased outside of the marketplaces or even employer-provided group coverage, for many low-income individuals and families, these costs are unaffordable. Thus, even with no premium costs, Medicaid, with expansion, is a more attractive option than marketplace commercial coverage.

Additionally, applicants for marketplace coverage are evaluated for eligibility for Medicaid benefits. Those accounts which are determined to possibly qualify for Medicaid benefits are electronically transferred to the Mississippi Division of Medicaid for further evaluation and a final decision on Medicaid eligibility. But without expanding Medicaid, low-income adults would be deemed ineligible, allowing the purchase of subsidized marketplace coverage.

So as a viable and preferred alternative to Medicaid expansion, the issue of disparate out-of-pocket costs for marketplace plans could be addressed in creative ways. Perhaps the state could work with the federal CMS to utilize Medicaid expansion dollars to cover some or all OOP costs associated with the commercial plans. Maybe the state’s hospitals would be willing to provide financial support as they will in absorbing the state’s costs associated with the Medicaid payment reforms proposed by Governor Tate Reeves and recently approved by CMS.

Another concern about Mississippi’s uninsured population obtaining coverage in the ACA marketplaces is the limited PPO network of hospitals and physicians included in the plans offered in the marketplaces. Presently, four carriers participate in Mississippi’s marketplaces. Notably missing is Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Mississippi, which has the largest health insurance market share and the most robust PPO. Patients pay less for services delivered by providers “in network.”

Additionally, most providers will not accept assignment of insurance benefits if they are not in the carrier’s PPO network. That typically requires the patient to pay out-of-pocket for services when rendered, file claims directly with their carrier, and wait for reimbursement, creating a hardship or untenable situation for many, especially those with low incomes.

Perhaps the state, private sector, clinical and hospital communities, and carriers could devise an acceptable system to expand the networks available to enrollees of plans sold in the marketplaces. This is KEY to positioning commercial marketplace coverage as a viable alternative to Medicaid expansion for low-income working adults.

Establish a program to fund commercial coverage for the state’s low-income working adults that would be eligible for Medicaid expansion

Yet, another concept that sounds a bit radical (see the title of this piece). The idea is to set up a way for private businesses, individuals, state government, insurers, and health care providers – essentially a melting pot of stakeholders – to contribute to a fund that would cover the cost of commercial coverage, again for those otherwise eligible for Medicaid should the state adopt expansion.

As with any out-of-the-box idea, there are numerous details to flesh out, such as administration of the program, including the process for application and approval, establishing transactional relationships with carriers, and a host of other elements. Perhaps private contributors to the fund could receive full or partial state tax credits as a financial incentive to participate. I believe it’s a concept worth exploring.

Other general health care policy ideas

Eliminate the disparate tax treatment of health insurance premium expenses

Health insurance premiums paid for by an employer for employee coverage are exempt from federal income and payroll taxes. Additionally, employees’ contributions to premiums reduce taxable wages before applicable federal income taxes are withheld.

This federal pre-tax treatment of employer-provided health insurance is not available for coverage obtained in the individual market, e.g., the ACA marketplaces except for those who are self-employed.

While the state can’t change federal law, state lawmakers should consider enacting law that would address this disparate tax treatment, allowing the cost of health insurance premiums paid by those who are not self-employed to be deducted from gross income in calculating state income taxes.

Reduce the cost of drugs by importing from Canada

For years, Americans have sought to purchase lower-cost drugs from Canada – either online or by traveling directly to our neighbor to the north. However, without proper government approval, the practice is largely considered illegal.

Recently the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the state of Florida to import drugs from Canada, in a move designed to drive down the cost the Sunshine State’s citizens pay for medicine. In addition to Florida, which submitted its application in 2020, numerous other states have also submitted similar requests to the FDA.

Predictably, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, an industry trade group, described the FDA’s decision as “reckless.” Canadian authorities have also expressed opposition.

Regardless, Mississippi should track this closely and consider applying to the FDA for the import of drugs from Canada to the Magnolia State.

Final Thoughts

The advances in medical science over the past few decades have been nothing short of monumental. Human innovation in treatments, procedures, drugs, and therapies has increased life expectancies, cured disease, and improved the quality of life. That’s the good news.

The challenge is that all the new care available today and in the future potentially adds to rather than bends the cost curve. As more care is invented, overall health care spending tends to rise, as people seek to “purchase” these newly available treatments.

As an example, the FDA recently approved two cell-based gene therapies for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD). Casgevy and Lyfgenia are estimated to cost over $2.2 million plus potential accompanying care. Of course, curing SCD in a patient should reduce the long-term cost of care to manage the disease, but the net economic effect is to be determined. Many people who suffer from SCD are unable to work full-time.

Any discussion about health care economic policy must include ideas on how to improve the health of our state’s population, a driver of overall costs. We should start by focusing on the state’s top ranking in infant mortality. Adoption of healthier lifestyles and wellness care (including proper prenatal care) would lower the incidence of disease, improve the quality of life, and drive down the overall cost of care for everyone.

Finally, our state is blessed with lots of smart people who want our citizens to flourish and our state to achieve its fullest potential. A healthy population and a thriving, robust healthcare system are essential to Mississippi’s success.

Mississippi’s elected leaders should commission a task force comprised of a “brain trust” of individuals and subject matter experts representing a cross-section of disciplines, including but certainly not limited to, health care professionals, hospitals, private companies (of varying sizes), insurers, state Medicaid lawmakers, community leaders, pharma reps, economists, and even faith leaders to devise practical solutions to Mississippi’s health and health care challenges.

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the views of SuperTalk Mississippi Media.