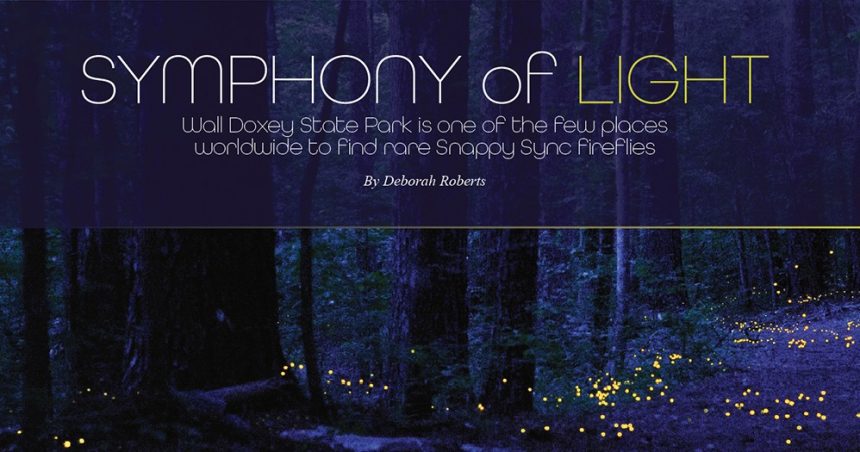

The following article was written by Mississippi Outdoors Magazine contributor Deborah Roberts

On a late spring evening in 2011, Jeff Davis, former park manager at Wall Doxey State Park near Holly Springs, got a call from a camper who was on a nature walk with about 75 other park guests.

“He said ‘you’ve got to get to the back side of the lake.’ I asked what was wrong, but he just said ‘you’ve got to get around here,’” Davis said. “When I pulled up, he yelled for me to cut my lights off. I asked again what was wrong.”

Still perplexed by the urgent situation, Davis obliged and turned off his truck’s headlights. “The next thing I know, there were thousands of fireflies all blinking at the same time,” he said. “The first time I saw that, I got goosebumps.”

And now the annual viewing of the Wall Doxey fireflies has become a popular event for park attendees. Before Davis retired in 2013, he estimates taking more than 1,000 visitors out scouting at night for the fascinating creatures.

“Everybody accused me of putting out Christmas lights,” he said.

The light show is spectacular but short-lived. “These fireflies peak around the last week of May or early June and they only last for a few weeks,” Davis said. “We still have some after that but not as many.” Between 8:30–9:30 p.m. is prime time before they taper off for the night. In 2012, Davis spotted the tiny sparklers on a trail about 100 yards or so behind the park’s cabins, and he has even seen some at the campground.

During his tenure, he worked with several individuals and organizations that studied fireflies at the state park. “Researchers studied the weather, what was blooming at the time,” he said, “anything that might affect them.”

Davis lives at Olive Branch, close enough for a firefly fix most nights of their season. “I still go every year to take pictures and try to video, which is extremely difficult,” he said. “It’s just a spectacular sight—thousands all blinking at the same time. Then they’ll stop. Then they’ll form a train, one blinking right behind the other, then go back to all blinking at the same time.”

Lynn Frierson Faust of Knoxville, Tennessee, grew up spending summers in Elkmont in the Smoky Mountains, a location known for its synchronized fireflies and has watched them her entire life. “I had never heard the term ‘firefly,’ I just knew ‘lightning bug,’” she said. Now Faust advises state and national parks about fireflies and serves as a scientific consultant with the likes of BBC Nature, the Discovery Channel, and National Geographic. In 2017 she wrote “Fireflies, Glow-worms, and Lightning Bugs,” the first comprehensive firefly guide for eastern and central North America ever published.

“I’ve spent the last 27 years researching them,” she said. “They have kind of taken over my life,” Faust said the first thing she learned is that there is more than one type of firefly; in fact, 125 species are reported in North America. Mississippi is home to at least 21 of these species.

After being contacted about Wall Doxey’s fireflies six years ago, she made the long trek there in 2017 and 2018, documenting eight different firefly species during her May visits. She also studied the history of the state park, because “if you don’t know the full history, then you can’t know all about the fireflies.”

The area’s cypress swamps were likely relatively undisturbed until European immigrants settled nearby in the early 1800s. “By 1840, Spring Lake was created from the many springs, and a four-story mill and millrace were built on lands that are now what is Wall Doxey State Park,” she said. “Twenty-two years later, this same area was devastated by the Civil War. The cypress swamp within Spring Lake has surely been destroyed many times and yet each time has regrown. The existence of the rare Cypress firefly and all the other lightning bug species at Wall Doxey State Park represents a victory for habitat restoration. Nature can recover if given the chance.”

Wall Doxey offers multiple habitats in a single location. “Some fireflies prefer to be out in the open, while some like to be along and over the water,” she said. “All species are very habitat-specific.” The Big Dipper, for example, comes out at dusk and likes open areas like the picnic and cabin areas. “If you grew up in Mississippi, it’s the one you probably caught in a jar,” Faust said. “They’re pretty, and they’re slow and lazy, so they’re easier to catch.”

Each species debuts at a specific time of year. “They only live a month or a little less, then they disappear but are replaced by another species,” she said. “In north Mississippi, it’s May and June for the most active species at once. You start seeing flashing fireflies in the southern-most part of the state around the end of February because the warmer part of the state gets active first. You probably have active firefly species all year round, but a good many species have lost their lanterns. In some species, the grownups don’t light up so it’s only the young ones we notice.”

Faust says Mississippi seems to have enormous numbers of an extremely showy species, Photuris frontalis, also known as Snappy Sync or in her opinion, “the mother of all fireflies.” “Snappy Sync in large numbers will absolutely knock your socks off,” she said. “Wall Doxey is the first place I heard about them in Mississippi.”

Faust says attentive observers can recognize each species by its flash pattern. “The Big Dipper makes a J-stroke every four to six seconds,” she said. “Snappy Sync flashes almost two times per second, very quick and bright on hot nights; once a second on cooler nights, yet extremely rhythmic. The hotter it is, the faster they flash. It’s like Morse Code and very species specific.”

Actually, Faust points out, it is only the male Snappy Syncs who fly around and flash. “They are like teenage boys— they show off and want everyone to see them,” she said. “The ladies are more demure. They stay in the leaf litter and only want one specific male to see them. A female will aim her light at the one male who catches her eye.”

Faust’s research method is “ID and release,” catching fireflies in a specially made insect net just long enough to identify one before letting it go. “It’s too hard to catch them by hand,” she said, “plus the net causes much less damage.” But for the rest of us, Faust offers this advice: “Just enjoy them. Nobody has to take it to the nerdy level I do.”